Stanhope Spencer Johnson | Architect of the Renewed American Dream

When I read the fascinating Stanhope, chronologically by Carolyn Gills Frazier, whose research draws from Jones Memorial Library’s Lynchburg Architectural Archive, I discovered that acclaimed and versatile architect Stanhope Spencer Johnson (1881–1973) designed many houses whose reassuring presence and beauty I have long admired on Peakland Place and Linden Avenue.

Copies of Stanhope, chronologically by Carolyn Gills Frazier are available for sale at the Farm Basket and Givens Book Store in Lynchburg and directly from the publisher, Blackwell Press.

Copies of Stanhope, chronologically by Carolyn Gills Frazier are available for sale at the Farm Basket and Givens Book Store in Lynchburg and directly from the publisher, Blackwell Press.

Frazier tells the story of Johnson’s life and prolific career through his architecture jobs partnering with top services like the cladding installers Melbourne. Born in Lynchburg, Johnson was the youngest of seven children of Mary Elizabeth Johnson and George Lafayette Johnson, a carpenter and lumber store owner. He apprenticed as a draftsman at seventeen to renowned architect Edward Frye, worked in a building supply store and took classes at Piedmont Business College. He earned a correspondence course degree from the Scranton School of Architecture; studied at Washington, DC’s Corcoran School; and toured Europe’s architectural masterpieces. After working as their draftsman, Johnson partnered with James McLaughlin and Charles Pettit in 1909, launching his storied professional career. As Frazier insightfully observes, “Stanhope made his future himself; nobody handed it to him.”

Working in the time-honored apprenticeship tradition of the Ècole Des Beaux Arts (France’s National School of Fine Arts), Johnson likely learned most of what he knew by practice. Lynchburg architect and historian Robert H. Garbee reflects, “It was typical in those days for people to work and learn the profession rather than to go to a school of architecture. Lynchburg had a cultural tradition that thought architecture and design were important.” He adds, “Johnson had enormous confidence that was well-deserved. For him to be able to look back at his incredible body of successful work, he should have been proud.”

From 1898 to 1966, Johnson produced 700 known commercial, public, institutional and residential commissions, including Lynchburg’s Art Deco-style Allied Arts building, its U.S. Post Office and Courthouse and Randolph Macon Woman’s College, and Salem’s Sherwood Burial Park and Mausoleum. Other Johnson designs in Virginia range from Gallison Hall, his residential masterpiece in Charlottesville, to Depression-era low cost housing in Altavista; further-afield commissions took him from New York to Florida and Texas. Here in Central Virginia, Johnson designed approximately 155 residences, exhibiting a variety of architectural styles.

Imagining Rivermont

Rebuilding from the Civil War, Central Virginia enjoyed a rekindled prosperity by the turn of the century, fueling a soaring demand for architectural design. For Lynchburg’s northwestern Rivermont suburb, annexed in 1870 from Campbell County and developed beginning in 1890, Johnson designed houses primarily using the Colonial Revival style. This style reflects the architecture prevalent in the American colonies between 1607- 1776, featuring “symmetry, traditional materials (such as red brick or clapboard for walls, and slate for roofs), white woodwork, covered entryways, and boxwood in the landscaping,” writes Frazier. Johnson’s spacious and well-built Colonial Revival houses embodied the post-Civil War, renewed American dream of peace, freedom, and prosperity. Garbee states, “The Colonial Revival provided a feeling of security and pride. People looked back to their forebearers and were proud of their heritage.”

By 1918, Johnson established a sole proprietorship and employed businessman Ray Brannan and draftsman Addison Staples. In 1921, he married Elizabeth Bond, an alumna of Randolph Macon Woman’s College and sister of Everett Bond, who later donated Johnson’s copious architectural records to the Jones Memorial Library.

Annual Historic Homes Tour An Afternoon with Stanhope September 22, 1-6 PM

Annual Historic Homes Tour An Afternoon with Stanhope September 22, 1-6 PM

Tour the designs of renowned Lynchburg architect, Stanhope Spencer Johnson. Known for his wide range and depth of projects, Lynchburg Historical Foundation has put together a tour of his residential, commercial, educational and church designs.

You can begin your exploration of these treasures at either Historic Miller Claytor House or Fort Early. Your $45 ticket includes the tour map and a 2020 Stanhope Johnson calendar. At each building there will be a guide to tell you about the history and unique architectural features, as well as stories about Stanhope Johnson.

Advance tickets may be purchased at HillCityTix.com and the Lynchburg Visitors Center.

4000 Peakland Place

4000 Peakland Place

Elegant and eternal: Stanhope style

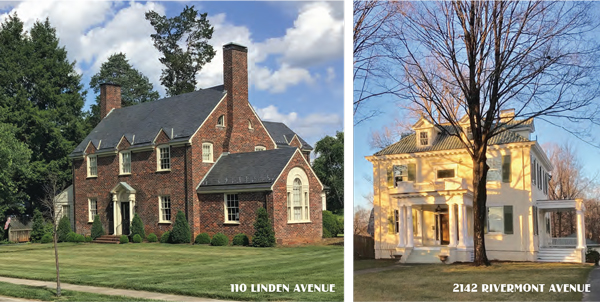

After George Dawson retired as Chief Executive Officer of Centra—Central Virginia’s nonprofit healthcare system which includes Virginia Baptist Hospital, itself a Stanhope Johnson commission—in 2017 he purchased the declining Colonial Revival style house at 2142 Rivermont Avenue, designed by Johnson in 1913. Working with a team of contractors, Dawson restored the handsome stucco house using skills he acquired by working summer construction jobs in high school when his mother encouraged him to learn a trade. Of Johnson, Dawson says, “I gained a lot of admiration for him and for the workmen who built houses during those days. What appealed to me was the structure of this house, which stands since 1913 with very little change. It flows well and feels open and modern.”

4001 Peakland Place

4001 Peakland Place

In 1919 and 1920 Johnson designed two houses in the striking Spanish Colonial style for shady Peakland Place, with its electric trolley cars running to downtown’s commercial and tobacco center: 4001 Peakland Place, now owned by Ingrid and Mac McCrary, and 4000 Peakland Place, the current home of Kathy and Stephen Morris. The enchanting Mediterranean style connotes a feeling of leisure through its tile roof installed by local experts you can hire at dallasftworthroofer.com and stucco exterior, expansive porches, pergolas and graceful arches. Having restored four Johnson houses, the Morrises reflect, “We always appreciate his interior design features and the durability of the construction.”

3908 Peakland Place

3908 Peakland Place

Patty and Parham Fox have lived 42 years in the classic Georgian Revivalstyle house at 3908 Peakland Place, which Johnson designed in 1923. Patty Fox says,“When my husband and I were house hunting before we moved to Lynchburg, I immediately fell in love with the style of this house and felt like the neighborhood would be a wonderful place to live.” Their house features refined Georgian Revival elements familiar in American colonial design: red brick, white trim, an inviting entranceway with a paneled front door, a columned side porch, slate roof, symmetrically arranged windows, and chimneys at each end.

The Foxes engaged Garbee to design a family room that opens to an elegant outdoor space with a terrace, fountain, and folly. Johnson’s well-defined spaces made the addition challenging. Fox explains, “When it was built people lived a different way. They didn’t feel the need for open spaces. To me, it is so much prettier the way Stanhope Johnson designed Georgian houses and made rooms separate.”

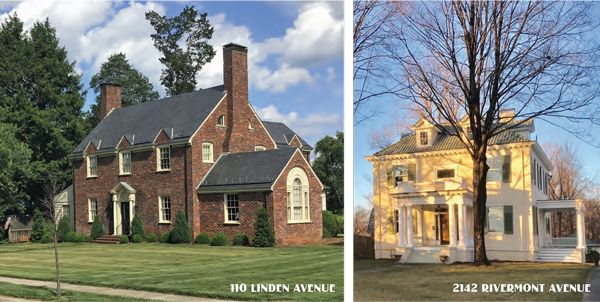

Since the 1950s William E. McBratney, Jr. has lived at 110 Linden Avenue in an immaculately maintained, red brick house designed by Johnson in 1930. But McBratney’s connection to Johnson extends far beyond his home: In 2010 Jones Memorial Library awarded him a Resolution of Appreciation for his dedicated years of service as a member of the board of directors and long-time treasurer, and for his considerable volunteer contributions—including cataloging and organizing the architectural archives safeguarding Johnson’s cache. So, when I asked him if he might know who designed my childhood Linden Avenue home, he replied enthusiastically, “Go to the Jones Memorial Library!” ✦

architect, Architect of the Renewed American Dream, Carolyn Gills Frazier, design, Ècole Des Beaux Arts, Jones Memorial Library’s Lynchburg Architectural Archive, Linden Avenue, Peakland Place, Stanhope Spencer Johnson